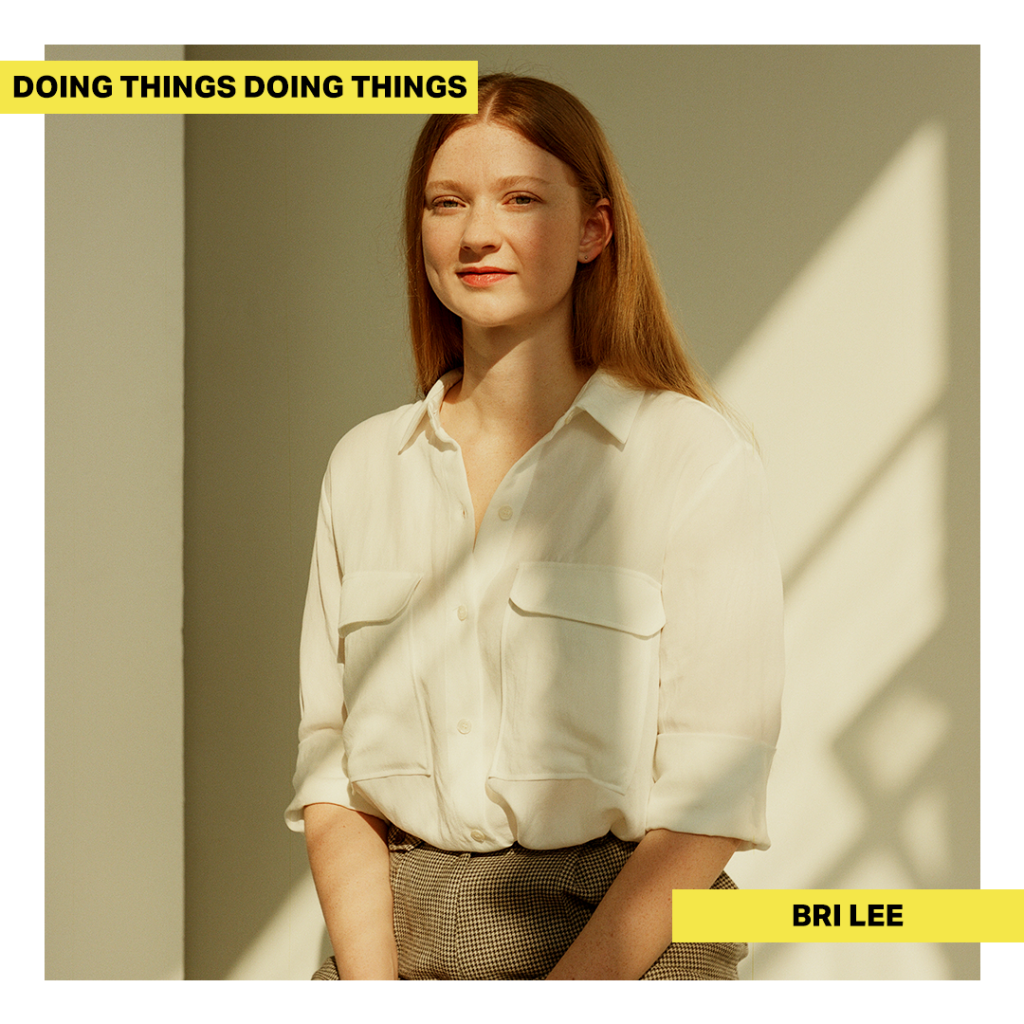

Author of best-selling Eggshell Skull, Bri Lee has just released her second book Who Gets to Be Smart. And just as she did with her debut, Lee uses the pages to take a sharp-eyed look at the flaws and inequities of Australian institutions – this time, it’s the education system.

Warning: Who Gets to Be Smart is definitely *not* a bedtime read! Lee’s revealing exploration of the elitism, privilege and politics baked into education will leave you fuming and ready to burn it all down. In Australia, who gets to be recognised, respected and harness the power of knowledge? As it turns out, far fewer people than you might think…

We spoke to Lee about the book, Australian inequality and why ‘kyriarchy’ is a term we should all be more familiar with.

Who do you think most needs to read Who Gets to Be Smart?

People who still truly believe that Australia is a meritocracy. The further I dug, the more I appreciated how so many facets of my life and so many things I currently enjoy were almost predestined because of the start in life my parents were able to afford to give me.

The important thing to remember about privilege is that it doesn’t mean you haven’t worked hard – it means you didn’t have the barriers that other people had. And you know, I work incredibly hard as well but the statistics don’t lie. Australia tells itself stories about social mobility that just aren’t true.

The book examines Australia through the lens of a specific concept: kyriarchy. What does it mean?

I find the easiest way to understand it is as a pyramid. In the same way that the concept of intersectional feminism takes the basic ideas of feminism a very important step further, kyriarchy takes the concept of patriarchy one step further and is specifically useful in looking at institutions.

When we talk about a kyriarchal pyramid, we’re talking about how a very small number of people at the top gain power and have a vested interest in keeping more people below them, and making sure that no more people can join them at the top. The reason they have power and enjoy sitting at the top is all about exclusivity.

The term was originally coined by seminal feminist theologian Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza, and when I first encountered it by speaking to my friend Omid Tofighian, who was the translator for Behrouz Boochani’s book No Friend But the Mountains. It’s a term that’s used to incredible effect throughout [that book].

How does that apply to Australia and our education systems?

Kyriarchy becomes very useful to apply to education systems, because “exclusive” private schools use their exclusivity as a selling point. It’s supposed to be a place about knowledge sharing and education, but it actually gains all its value, prestige and power from the number of people it excludes rather than the number it includes.

The example in the book is when the Ramsey Center for Western civilization wanted to gain a foothold at the University of Queensland. There were a huge amount of protests against it, but then they allowed it to go to a secret blind vote of the Senate. So you have to ask, who’s accountable for [the vote]? And it just explodes into a large number of like anonymous bosses – even the way universities are run like corporations, who’s the boss of the boss of the boss? And corporations in Australia explode into an infinite number of shareholders.

So the status quo is allowed to perpetuate and nobody has to put their hand up and take responsibility for the unfairness that continues. It’s a complete lack of accountability, and yet it’s nobody’s fault.

Do you think that these places are exclusive by design?

Absolutely. That’s why there are large sections in the book about the Ramsey Center, because it’s the perfect extreme example to show how it takes to an extreme what everywhere else does to varying degrees.

They went with their hundreds of millions of dollars to the University of Sydney and asked if they could set up Ramsey scholarships there. The University of Sydney said no, but went back with a counter proposal that would see thousands of students benefit – sort of spread the riches around more easily to give funds to a wider distribution of students. And the Ramsey Center said no, because they’re not actually interested in benefiting lots of students. What they’re interested in is creating a hyper-exclusive small group of people, and the value of what they get in being able to call themselves ‘Ramsey scholars’ is the very fact that there are only a few dozen of them.

They are not interested in actual knowledge sharing or sort of wider goals of education. They’re interested in privilege and legacy.

What is it about us as people that means when we get into an exclusive space, like Oxford, we want to maintain the exclusivity rather help make it accessible to others?

That’s a big, chewy philosophical question about human nature. But I would say people’s conflicting interests and desires become most obvious when they are trying to make decisions for their children. Individual parents feel a very real obligation to put the interests of their children first. Whereas in my personal opinion, the State has an obligation to treat all children equally.

And so what you have is two starting points for ideas about either philosophy or policy that are in direct competition with each other. The problem is that education policy and education funding is based on the financial interest of parents rather than the educational rights and interests of children. So now you have half or secondary school students in Sydney and Melbourne at private schools, while the other half are at state schools. But well over 80% of students who have some kind of higher needs, who need extra resourcing, are at the state schools!

It’s been getting worse and worse since [John Howard’s Prime Ministership]. And I think one of the reasons is because of how aspirational Australia is. We have this huge middle class – the aspirational middle-class is just like a national identity. It’s a defining part of what Australian culture is. And in some ways it’s fantastic, because it manifests in a kind of hardworking attitude.

But on the flip side, the hardworking belief can be toxic in that we presume anyone who hasn’t “got it good” just didn’t work hard enough. And we presume that anyone who has it really good must have worked really hard. And I do not agree with either of those presumptions.

What do you think has to change if we want to shift these problems in Australia?

I believe all children have a right to a well-resourced education because Australia is such a rich country. There is no excuse for us not to consider a high quality education as the right of every child.

And then when it comes to the institutions, I think the state has an obligation to provide the resources that children need to learn. If a private group wants to provide an alternative [to public schools], so long as the children are still meeting the milestones, they can set up alternatives to state-run schools. But unless they’re going to accept any and all students they shouldn’t get government funding. It blows my mind that we will still give them public money to do so.

How do we change that? Is there an education policy the government should be implementing right now?

If I could pick one thing, it would be to have transparency and reporting requirements for any schools that do get government funding.

There were documents leaked to the ABC in 2020 that showed the Catholic school system in NSW for years and years has been taking money allocated to them to [support] poor students in school, and instead giving it to rich students. At the directive of the Bishops. It almost makes me speechless.

But what it tells us is that the bishops and the people running the Catholic school system know that if they can’t keep the schools affordable, even in rich areas, they will lose enrollments to other options and potentially also government-run options. We potentially could solve a large part of this problem if we actually just required the enormous Catholic school system to run transparently.

You attended a well-resourced private high school yourself, and have access to a lot of privilege that many others in Australia don’t. How did you reconcile that while working on the book?

Researching for this book made me really convinced that, as somebody to whom doors of a university are essentially open because of my educational background, if I’m going to take either the [PhD] money or the kudos, I have a very real obligation to only do student that has a positive and broader impact.

And the book is the reconciling of that, essentially. It’s important to not think that gendered crime is only a women’s issue, not to think that racism is only an issue for people of color, that class is only an issue for poor people.

I can interrogate these systems in a way that I can, because I have access to the inside of them. And so for me, it’s like a moral obligation to shine a light on the inside, the same way that some of the people who’ve been most outspoken against Rhodes’ legacy are former Rhodes scholarship recipients.

What’s the one message that readers should take away from Who Gets to Be Smart?

What I’m personally most grateful for, was that I had previously just outsourced my priorities to these institutions. And I had not been able to realize that it was a significant source of my insecurity and unhappiness that I had just accepted a criteria sheet that actually didn’t align with my personal beliefs and where I wanted my life to be going.

So I would say the one takeaway is to allow yourself the time and space to sit with and examine what you have, what ideas you have inherited. And decide for yourself, whether that is actually the type of person you want to be, or whether the only reason you’re continuing to go along with it is because it’s what you were told. That applies to the external stuff about class and achievements, but also the very intrinsic stuff like what you even think is “intelligent”.

Who Gets to Be Smart is available now.