Since the beginning of the pandemic, governments and the media have provided daily reports on infection and death rates. But there is a grey area in-between – what about the people who contract Covid and don’t recover? In the United Kingdom alone, the Office for National Statistics estimates 892,000 people have what’s become known as “long Covid” with symptoms lasting more than three months. Numbers like this make it clear, in this pandemic, death is not the only outcome that counts. Here’s what we know about long Covid so far, who it affects and how it could have a long term impact on our world.

What is long Covid?

The term long Covid was first used on Twitter by researcher Elisa Perego to explain her ongoing symptoms after infection with the coronavirus. It was quickly adopted by the patient community, who were searching for a name to describe the debilitating condition medicine had no answers for.

In the United States, the Center for Disease Control defines long Covid as “a wide range of new, returning, or ongoing health problems people experience after being infected with the virus. These conditions can present as different types and combinations of health problems, for different lengths of time”. If you think definition sounds broad, try listening to people’s stories – or you can read two below. People recount a kaleidoscope of long Covid experiences, demonstrating how this illness affects everyone differently.

Severe fatigue, post-exertion malaise (the worsening of symptoms after physical or mental exertion), and cognitive difficulties (often called brain fog) appear to be the most common symptoms reported. The condition has the potential to affect every system in the body and a patient-led study of 3,762 people lists more than 200 unique symptoms.

The time it takes to recover is variable too. Some people get better after several months, while others go on to develop long-term disability. Scientists don’t understand the cause and, so far, no evidence-based treatments exist – though research into the condition has begun.

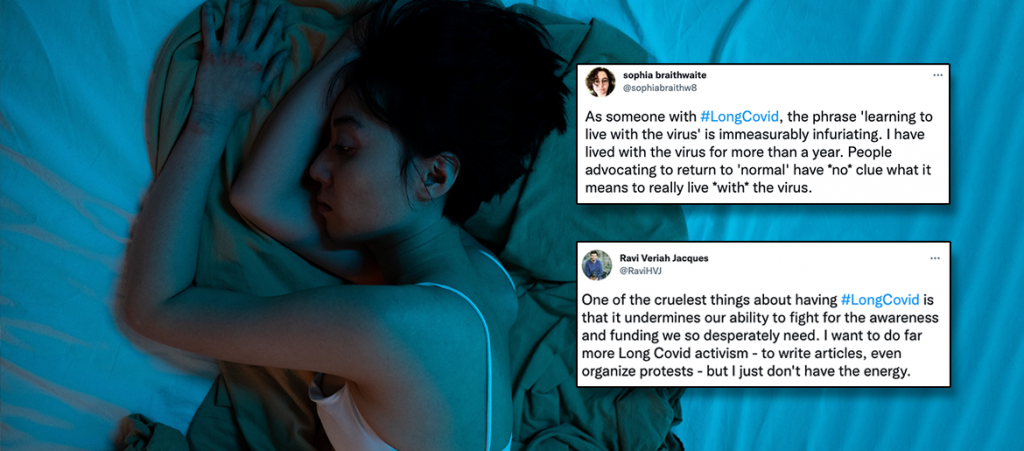

As someone with #LongCovid, the phrase ‘learning to live with the virus’ is immeasurably infuriating. I have lived with the virus for more than a year. People advocating to return to ‘normal’ have *no* clue what it means to really live *with* the virus.

— sophia braithwaite (@sophiabraithw8) January 6, 2022

Who does it impact?

As with all things COVID-19, it’s very difficult to know true rates but it’s reported that somewhere between 10 – 30% of people who contract the virus experience long Covid.

Early research indicates that countries like Australia with high rates of vaccination could see lower rates – but again, it’s not yet clear. David Putrino is an Australian neuroscientist and Head of Rehabilitation at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York. Since the pandemic began, he’s been working closely with long Covid patients, seeing 50-100 people each week. He told Nature the condition is “noticeably less common [in vaccinated] than in unvaccinated people, but it’s still there”. A recent study found the risk of long Covid was halved after two doses of the vaccine.

Like other post-infectious diseases, women seem more likely to experience long Covid. Dr Melissa Heightman runs the post-Covid care clinic at University Colleges London Hospital. She told The Guardian “around 66% of patients have been women. A lot of them were in full-time jobs, have young children, and now more than a quarter are completely unable to work because they’re so unwell. Economically, it’s a bit of a catastrophe.”

Real long Covid stories

Sophia Braithwaite was only 18 when she caught Covid in the first wave of March 2020. Her initial infection was so severe she couldn’t breathe, and it felt like her lungs were “badly bruised”. She recovered but developed long Covid several months later. “One day out of the blue, I had this really bad chest pain. All my symptoms returned and from that point on, I just got progressively worse,” she says. Sophia was completing her high school exams at the time, and recalls having severe neurological symptoms. “I remember sitting an exam and thinking, I don’t remember a single thing I studied, it’s all gone from my brain. It was one of my lowest moments because I felt like I was losing my mind.”

Sophia also said her symptoms are cyclical and unpredictable, staying for a month and then disappearing for a week or two. She describes chest pain that burns like “antiseptic on a cut”, severe breathlessness and night sweats so intense, she wakes up “completely drenched”.

In contrast to Sophia, Ravi Veriah acquired long Covid from an asymptomatic infection. “I didn’t have any acute symptoms at all, I just started feeling very, very tired. I only realised it was long Covid when my sense of smell and taste disappeared”. At the time, Ravi was 22 and getting ready to start his Masters in International Relations at a prestigious university. “I felt so fatigued, it felt like my body was being chained down.” Having deferred his studies, he now spends 16 hours a day resting in bed. “It hurts to think of my life before this. This thing has derailed my life in a way I never saw coming. Suddenly your whole world shrinks.”

There are concerns that, as long Covid appears to occur in women more frequently than men, patients will will have to fight for credibility within the medical and research communities. Already, Sophia has experienced gender bias from doctors who refuse to see past her history of mild anxiety. “Even with the nicest doctors, I get the sense they’re thinking, well you’re young and you’re female and you have a medical history of anxiety. That must mean this is all in your mind.”

One of the cruelest things about having #LongCovid is that it undermines our ability to fight for the awareness and funding we so desperately need. I want to do far more Long Covid activism – to write articles, even organize protests – but I just don’t have the energy.

— Ravi Veriah Jacques (@RaviHVJ) January 6, 2022

Why we need support for Long Covid patients

Historically, people with post-infectious disease have been stigmatised by medicine and denied access to much-needed treatment and support. I know, because I’m one of them. Five years ago, in a pre-pandemic world, I acquired ME/CFS after a virus and exposure to toxins. Much like Sophia and Ravi, my life changed dramatically, and since then I’ve had to fight to be believed and to access Australian healthcare and disability support. Like long Covid, ME/CFS is a complex and disabling disease that’s long been ignored by the medical community. Forty years after it first came to attention, there is still no diagnostic test or approved treatments for the estimated 17 million people affected worldwide.

The sheer scale of long Covid, combined with its public profile, makes me think Australia’s healthcare system will be forced to recognise this disease. But I have no doubt the burden will fall on patient activists to pressure our Government to invest in research and investigate potential treatments. Until this happens, patients will be left to fend for themselves. “Even the current gold standard in long Covid care doesn’t come close to what long haulers actually need,” says Ravi. “I think only a small number of doctors and scientists appreciate the gravity of our situation. In the years to come, plenty of people are going to be shocked by the scale and impact of long Covid.”

Further reading:

- Long-haulers are redefining Covid-19 on The Atlantic

- Long Covid isn’t as unique as we thought on Vox

- Long covid is not rare. It’s a health crisis on The New York Times

Comments are closed.