Cost of living was the defining issue of the 2022 federal election. And with good reason, because it’s getting expensive out here. But in order to really grasp the constant stream of media and opinions about the strategies being employed to address the issue… we need to understand what the term ‘cost of living’ really means in Australia. What factors are involved, how it’s measured, why it feels so painful right now… and what can be done to make life a little more comfortable for us all?

We’ve done our very best to break it down in a simple, straightforward way.

UPDATED: 15 June 2022.

How is the cost of living measured in Australia?

Let’s start with the very basics. ‘Cost of Living’ refers to the amount of money a household needs to be able to afford the goods and services necessary to maintain a general standard of living. Evaluating the cost of living involves two factors: how much stuff costs vs how much money you make.

First, how do we suss out the cost part of the equation? The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) uses two metrics: the Consumer Price Index (CPI) and Living Cost Index (LCI). CPI is the main figure used when talking about cost of living, so that’s what we’ll focus on here.

To calculate CPI, the ABS collects prices for a range of goods called a ‘basket’ (like a shopping basket full of the things you need). Items in the basket fall into 11 categories: alcohol and tobacco; clothing and footwear; housing; furnishings, household equipment and services; health; transport; communication; recreation and culture; education; Insurance and financial services. Then they add up the total price of the basket on a certain date, and compare that price to the previous time period. CPI is really a measure of the change between the two prices in a set period (i.e.: 2021 vs 2020).

When the measured change in these prices is an increase – that’s inflation.

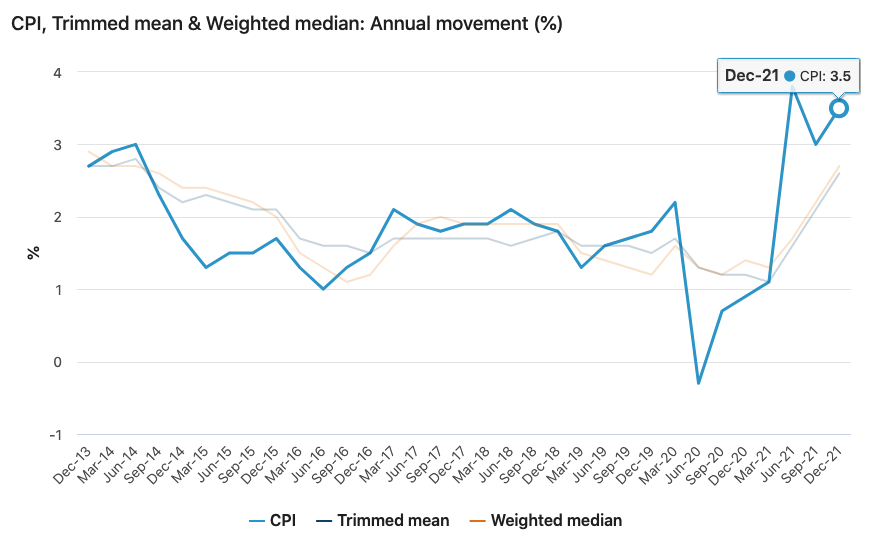

In 2021, the CPI increased by 3.5% – so, Australians paid 3.5% more for that basket of goods than they did in 2020. We also paid 1.3% more for the basket in Oct-Dec 21, than we did in July-Sept 21.

The second important factor in cost of living is: wages. The ABS also measures wages growth (Wage Price Index), and the latest data shows Australian wages increased by 2.3% in 2021. That figure has been consistently shrinking since 2008, and comparing wages growth with CPI shows why cost of living is a problem in Australia right now.

The logic is this: if your weekly wage increases by $100, but your weekly expenses also increase by $150, then your real income hasn’t really grown at all… you’ve actually gone backwards. That’s what happened in Australia: the 2.3% wages increase is less than CPI/inflation of 3.5%.

Editor’s Note 15 June: Today, the Fair Work Commission increased the minimum wage by 5.2%. Albanese’s new Labor government had advocated for this, as one of their key election promises. While welcome news, the inflation rate in March alone was 5.1%. This increase will very soon be outweighed by inflation again, as rates are still rising. Think of this move as necessary to stop minimum wage workers from sliding even further backwards than they already were – it’s not a solution to the problem of rising costs.

Technically, our wages have shrunk and life has gotten more expensive. The struggle of just living is real.

How do the Reserve Bank of Australia and cash rate relate to this?

The RBA’s job is to keep inflation (increasing CPI) consistently in the 2-3% range. Steady inflation over the long term is a sign that the economy is growing. But if the inflation rate gets too high or too far ahead of wages, it can cause hyperinflation and crash the value of the Australian dollar.

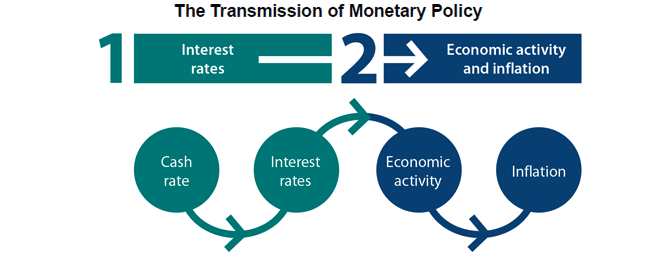

One of the ways the RBA can affect inflation is by setting the cash rate (the interest rate on the overnight loans between banks). The RBA meets on the first Tuesday of each month to decide whether they’ll raise, lower, or leave the cash rate where it is. In turn, the banks adjust their interest rates for consumers, which affects how much people can spend, which impacts inflation.

On May 3, the RBA raised the cash rate for the first time in 10 years – a clear sign that, yes, inflation is getting out of control. It raised the cash rate by 0.25% (to 0.35%).

In theory:

High interest rates = reduced spending, therefore lowers inflation.

Low interest rates = increased spending, therefore raises inflation.

But it’s not that simple. Banks don’t always change their interest rates to match the cash rate, and high interest rates do increase mortgage costs for homeowners. The impact of cash rate on the cost of living is also delayed – the RBA estimates that it takes up to two years for a cash rate change to affect inflation. It’s not a quick or comprehensive fix.

In Australia, inflation has remained within the 2-3% target range since 1993. Success, right?

Why is the cost of living in Australia an issue right now?

Measures like CPI, inflation, cash and interest rates don’t account for how cost of living changes affect different groups of people in different ways.

The most obvious is income level. A 3.5% increase in expenses will not affect high income households as much as low income households. Wages and prices also vary regionally – not only state by state, and suburb by suburb, but also higher-earning metropolitan vs lower-earning regional and rural locations. The ABS’ Selective LCIs is one way of looking at the impact on different groups, but is still very limited, general and doesn’t take geography into account.

Highest 20% Household Weekly Income After tax | Lowest 20% Household Weekly Income After tax |

$4166 | $592 |

ACOSS Inequality in Australia 2020 report

On top of that, each product item and category has a different rate of change.

For example, even before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, automotive fuel experienced the biggest annual price increase in the basket at 32.3%. Dire. Yes, fuel prices affect everyone, but some will feel this pain more than others. An inner city resident who takes the bus into a CBD office might see their public transport fees increase; those more reliant on cars, living in outer suburbs, rural and regional areas, or in cities with poor public transport (hi, Perth and Hobart) will see a bigger jump in their weekly expenses. For low income households, what happens when the price increase makes it too expensive to get to work?

Similarly, an increase in childcare costs will naturally affect parents of young kids more than parents of teens or who are child-free.

Indicators like CPI are helpful for looking at macroeconomics, but aren’t as useful for explaining who is most affected by cost of living increases or how to help them.

How much control does the government have over cost of living?

Governments can change the impact of the cost of living by making policy decisions relating to how much stuff costs, or how much you make. Some strategies are more effective than others.

Below is a general list of the type of policies that have influence, but there is one caveat. Just as climate action policy can only be meaningful if it includes closing existing fossil fuel power stations by 2040, the only cost of living announcements we should take seriously are ones that substantially help people on low incomes. Rising cost of living always affects low income households first and the most. Policies that reduce and subsidise costs for high incomes and the business sector might claim to help to everyone else, but trickle down economics is proven not to work.

How Governments Can Lowers Costs

- Social welfare: Paying for some of the absolutely essential costs so they are free or very cheap, especially for low income and vulnerable groups. Examples include: social housing, schemes like rent assistance, Medicare and mental health care plans, and the National Disability Insurance Scheme.

- Subsidies: Subsidising the cost of particular items with government funds to make them a bit less expensive. For example, first home buyers grants.

- Funding & investments: Putting money into businesses in key industries, so they can grow without increased costs and in theory, don’t pass those costs onto consumers.

- Taxes: Some taxes (including GST) are included in the CPI basket, so changes to these directly affect the cost of goods.

How Governments Can Increase Wages

- Public sector wages: Wages in the public sector (i.e.: government) influence the wages private business pay. Jobs in the public sector account for around 14% of jobs in Australia, and are typically paid at higher rates than the equivalent private sector jobs. They set expectations about what a good wage is, and research shows a link between public servant salary caps and decreased private salaries. This suggests that government policy to increase public sector pay could also drag private sector wages up with it.

- Minimum wage & worker entitlements: Setting (specifically, increasing) the minimum wage would increase the baseline amount that Australian workers receive. This also applies to the legal entitlements that employers must pay their workers – for example, paid sick leave for casual workers being trialed in Victoria, and requirements being discussed for gig workers.

- Social welfare: Providing additional income to low income and vulnerable groups, so they have more money for essential and discretionary spending. Examples include: Programs like Youth Allowance and JobSeeker, Age Pension, veterans benefits.

- Income tax policy: Lowering income tax rates, especially for low-to-middle earners, leaves more money in their pocket to spend.

The government doesn’t have total control over what things cost – fuel is one example. Australia’s fuel excise (a type of tax) is $0.44 per litre. The cost of fuel is now so high that the government is considering removing the excise, which will help in the immediate term but won’t stop the overall rapidly rising cost of fuel. There are other things they can (and should) do to combat this cost. One strategy would be to reduce the cost of alternatives – in this case, electric vehicles. Irrespective of the climate benefits, the goal would be to make electric passenger vehicles a realistically-priced alternative to internal-combustion engine passenger vehicles.

Ok, that’s it! If you still need more info, you might need to talk to an economist.

Comments are closed.