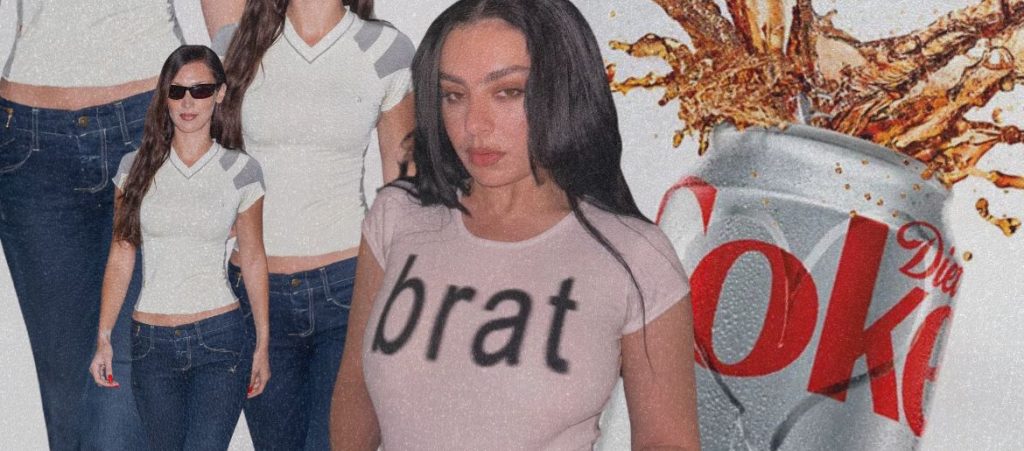

As someone who has lived with an eating disorder for almost 10 years, the moment low-rise jeans were “back in style” was the moment I picked up on the shift: a revival of the glorification of the thin body that I naively thought we had started to move away from. Throughout 2024 the idea has been picking up steam, through the endless stream of trending terms like “pilates arms”, “cortisol face”, the resurgence of Diet Coke on social media and, perhaps most pervasively, embedded into one of the biggest cultural moments for young people this year: brat.

Charli XCX’s record-breaking ‘brat’ album drop saw a full-fledged revival of the indie sleaze aesthetic, which has been threatening to creep back up on us since at least in 2021. If you look up brat on social media, the top images share a common theme: thin, seemingly white women in white tank tops with no bra, low-rise short shorts or jeans, black boots, and, of course, an accessory adding a touch of the iconic brat green.

There is nothing inherently wrong with these clothes; trends like low-rise jeans come in and out of fashion every couple of decades. However, it is the idealisation of thinness when we wear such clothes that is terrifying; the way aesthetic ideals like brat exclude those with bigger bodies or who are not white.

Of course, brat is certainly not root cause but of of the many trends currently glorifying thinness.

Maggie Zhou, a slow fashion advocate and influencer, told me she sees trends as “unavoidable” and is interested in “how they speak to our wider culture.” Zhou also has Chinese heritage, and while she doesn’t see this as impacting her participation in trends, she says that it has impacted her relationship with fashion more broadly.

“Immigrant, frugal mindsets of caring for clothes and not buying more than necessary have informed my sustainable fashion stance,” Zhou says. “Apart from that, I feel like my thin privilege and disposable income are the biggest factors that allow me to take part in fashion trends with ease.”

In discussing the potential reemergence of thinness and her experience working at various media outlets, Zhou sees “conversations around body diversity as lacking and inconsistent; we praise a brand, criticise another, and then repeat… Fatphobia in fashion, and in general, cannot be fixed through band-aid approaches like one-off magazine covers featuring plus-size women.”

In 2021, April Hélène-Horton, aka Bodzilla, was Australia’s first plus-sized model to appear in a bikini on a billboard. At the time, she told 9Honey,”I was the first fat chick on a billboard, and I don’t want to be the last.” However, it appears that Australia has yet to truly champion body diversity and platform plus-sized models and fashion since.

For example, AFW 2022 was the first time in AFW history that we had a curve-edit runway dedicated to plus-size fashion. However, the curve edit did not return in 2023 or 2024, and there was no increase in plus-size fashion across the show. Instead, Vogue Australia’s analysis of the Australian Fashion Weeks found that at AFW 2024, 1.1% of models were plus-size and 8.7% were mid-size. This is despite the average Australian woman wearing a size 14 to 16.

This issue is not confined to Australia. In February 2023, the number of plus-size models and size-inclusive runway shows took a nosedive, with the former dropping by nearly 24%. It was only in February 2024 that New York FW had its first plus-size show.

Is this the ‘re-emergence’ of thinness, or as Zhou says, is it that “we weren’t making solid improvements, to begin with” in creating the long-term changes necessary to support real body diversity in fashion and culture? Likely the latter, although she also notes there have been positive changes: “We have the vocab and knowledge to point out what’s problematic, like brands reducing their size range and the insidious use of Ozempic.”

In an interview on the Figuring Out 30, Hélène-Horton spoke about her own experience with weight loss surgery almost a decade ago, at a time when diet culture ran rampant, showed her that you can “change what’s not good about your world, without changing your weight.” Hélène-Horton has talked about the intersections between anti-aging cosmetic procedures and weight loss surgeries and the glorification of thinness, where it is claimed that this is what we need to be “healthy and youthful.”

These procedures are one amongst several promoted by the TikTok algorithm to millions, capitalising on the vulnerability of mostly young, impressionable women and non-cisgender heterosexual men. From buccal fat removal to so-called ‘cortisol face’ (explained as puffiness in the face caused by stress), it feels like my algorithm is telling me to get rid of any bit of my skin that protrudes, every bit of cellulite, every smile line and forehead crinkle created from the emotions I experience.

Hélène-Horton states that advocating for change should come from those with privilege or a platform, and talks about her own privilege being a light-skinned person of colour. It’s also true of my own privilege as a straight-sized person, which means I can see the negative impacts of the exclusion of plus sizes without feeling the direct impact.

Zhou also states that “we shouldn’t be giving too much air time” to the trends on our For You page, as they “feed off of buzzy-sounding insecurities and surgeries” and merely inflate the fixations.

It is clear that thinness is rife in almost every facet of life, whether we are seeing a reemergence or it never really left us.

Smart people read more:

Diet Coke’s Social Media Resurgence Is Another Sign of the Latest “Thin Is In” Wave on Teen Vogue

New Medium, Same Problems: Fashion Content Looks Exactly the Same in the Metaverse on Zee Feed

The Victoria’s Secret runway has returned, but is there still space for it? on Vogue Australia

Comments are closed.