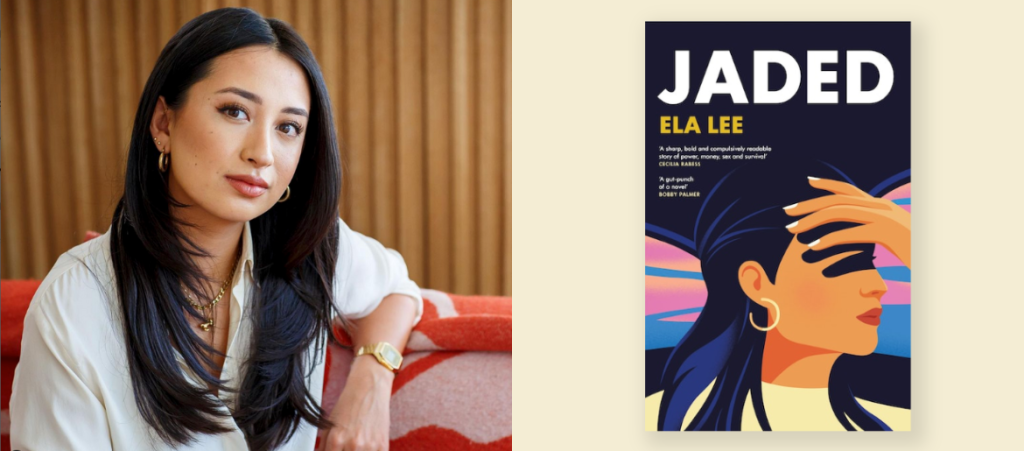

Ela Lee has written one of the most anticipated novels of 2024, Jaded. And even though it’s set in London, the story and themes couldn’t be more relevant to the reckoning of gender, wealth, race and consent that Australia is experiencing right now.

Here’s the story in a nutshell: Jade is the high-achieving only child of Korean and Turkish immigrants. She is a living embodiment of the model minority myth – climbing the ladder in corporate law, generational wealth boyfriend, loyal daughter. But when she wakes up the morning after a work event naked, bruised and in physical pain, with no memories of the night before, her entire life begins to unravel. You can see where this is going…

I spoke to Ela about writing the confronting aftermath of ‘grey area consent’ and why we can’t ignore race and class when talking about assault.

Crystal: Jaded tells a remarkably similar story to the Brittany Higgins case, which has brought a real reckoning around consent, sexual politics and power dynamics here in Australia. Is that conversation happening in the U.K. too?

Ela: In the U.K. – but I think this could apply to Australia and even the US as well – the media discourse tends to treat assault as this single event that almost exists in a vacuum. And the majority of effort and attention is focused on the perpetrator and the specifics of the incident itself. There’s very little discourse on what happens to a victim afterwards and how it goes on to change the course of their lives.

I have thought that about the Brittany Higgins case – that the aftermath of what’s happened to her doesn’t seem to be discussed as much as the actual events themselves. That’s the case probably across the board – institutionally, healthcare-wise, criminal justice-wise. We have such a long way to go in terms of understanding what it’s like to live with something like that, day after day.

The book paints such a vivid picture of Jade’s unravelling – it’s just immediately tense from page one, and I felt like I was trying to piece things together with her. You’ve spoken about writing the initial draft being very cathartic, but what was it like to go back and edit that?

It was very, very emotional and, like, tiring because the whole purpose of an edit is to be as self-critical as possible. When it came to Jade’s internal unravelling, her memory loss, the fragmentation of what she remembers and what she doesn’t, I felt a real responsibility to portray tha as authentically and fairly as possible. Jaded touches on what a lot of people like to call ‘grey area consent’, or blackout sex, which can be a lot more uncomfortable to talk about because it’s not black and white. I was really going over the aftermath of it with a very, very fine tooth comb, making sure that it was as fair and balanced to Jade as possible.

How important was it to you that this story tackled race as well as sexual and gender politics? It’s another element that’s just not often brought into these conversations…

It was a non-negotiable for me. It goes back to what I was saying earlier about assault being treated as a singular event, when actually it can never be that – it’s always situated within the wider context of somebody’s entire life, which inevitably touches on their race and their class and their gender. When something like that happens to you, there’s no way for it not to be dynamic with your race, your class, the varying resources available to you in the aftermath and how believable you are perceived to be. A lot of these things are dependent on profiling due to your race.

In order to unpack one question [about consent] you have to unpack them all together.

There’s a lot of tension around the idea of ‘security’ in Jaded, where immigrant parents and grandparents want us to find financial and social security in elite spaces, but those can be some of the most dangerous environments for us to be in due to our race.

100% – it comes down to the model minority myth, which is just if you keep your head down and you’re as hardworking as possible and you’re really quiet and you never complain, then maybe your host country will finally accept you and treat you as one of their own. I was born and raised in London and I’m still very much perceived to be an immigrant, even though I’m not. It is a myth ultimately. You can kind of spend your whole life moulding yourself to be the right type of person, but all of that is a construction and it will crack at the first hurdle.

Jade really does strive to be the model minority and that stereotype became her self-fulfilling prophecy, it became the standard for her to meet. It’s the constant othering that I wanted to capture – the constant feeling that you can try as hard as you want, but you are never fully gonna fit in.

The portrayal of Jade’s parents is one of my favourite parts of the book because it’s so real and tender, and it clearly reflects your relationship with your Korean mother and Turkish father. How have they reacted to this portrayal of what it is to be a first generation striver in a Western country?

So, my mum hasn’t read it. Fingers crossed, it might get translated to Korean and she might read it, but she hasn’t yet. But my dad has and it’s almost been a moment of… I don’t wanna say understanding, but I think he felt very touched by it.

Quite a common rhetoric between immigrant parents and their children is almost like, ‘Your life is so much better and easier than mine, you have all these opportunities that I don’t have and you have to make the most of that.’ For my dad and my friends’ parents who are also immigrants, they saw it through the other side of the lens – this is what it’s like to grow up with your feet in two different worlds and learning that constant shape-shifting of your personality. It’s a different level of pressure which doesn’t mean one is worse or better, but just that the experiences are different. It’s been a bridge to understanding in that way.

It’s a mixture of feelings, but I’m sure it’s the same for you, this joy they get out of seeing you write about the things that mean a lot to you.

There are a few characters I want to touch on – Jade’s wealthy boyfriend Kit, his mum Angie and best friend Ollie. They are not overtly bigoted or misogynistic characters, but they say some horrific things to Jade. Do you think people will recognise their own behaviour in these moments?

I would hope so! What I try to get across with those characters is that they are, in their own way, well-meaning. They’re not necessarily malicious, they would never think of themselves as racist or sexist or anything like that. But when you are coming into these spaces, you do have to be mindful… You know, that scene where Kit brings up the Korean War [to Jade’s Korean mother] – that is real people’s trauma, real people’s history and loss. You can’t just bring these things up to show how well read you are! It’s just small examples to hopefully give readers a flavour of what it’s like to be on the other side.

If there’s a flicker of recognition with these characters, it’s time to pause for reflection!

Or even if as a reader you feel conflicted about the events between Jade and Josh [the co-worker who assaults her], the intention is to create a discussion around it. My hope is that there is a greater level of empathy. Specifically talking about assault, people are very quick to put their two cents in and make a judgement of the situation. But hopefully after reading Jaded it might give people some pause, and increase the understanding that these situations are inherently complex and nuanced. We should spend more time empathising with the survivors rather than sensationalising the perpetrator and the circumstances around it.

Jaded by Ela Lee is out now.

Smart people read more:

By The Time Schools Talk About Consent, Kids Have Already Grown Out of ‘Leaking Nudes’

Yassmin Abdel-Magied On Tackling Social Change Like an Engineer

Why the Statistics Around ‘False’ Sexual Assault Claims Are Even Lower Than We Think

Comments are closed.