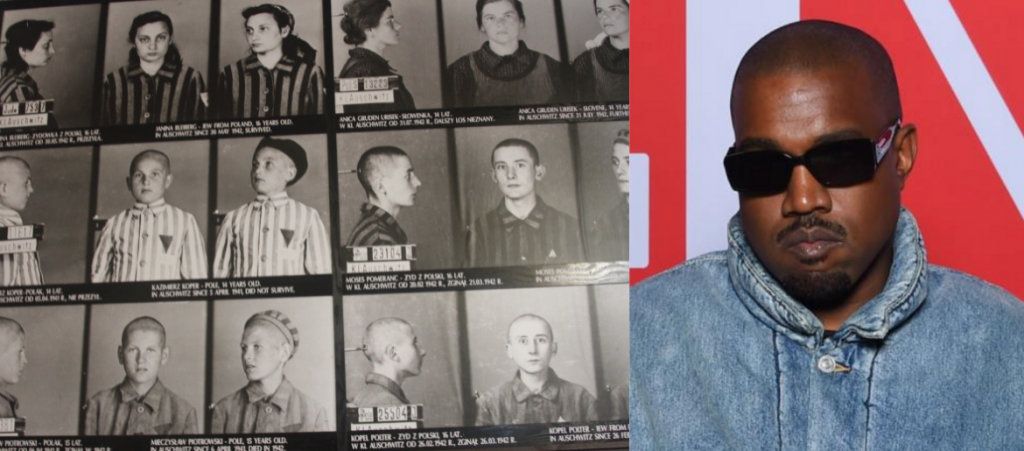

Over the past five years, there has been a documented increase in antisemitism online and around the world. The Internet and its ability to amplify hateful ideas with terrifying speed has a lot to do with it. Alarmingly, a 2022 survey found that 30% of young Australians have ‘little to no knowledge’ of the Holocaust. That puts us at risk of falling for Holocaust distortion – a common tactic for planting the seeds of conspiratorial ideas about Jewish people and spreading Neo-Nazi ideology.

International Holocaust Remembrance Day (on 27th January 2023) is a day to not only honour the victims, including the six million Jewish people murdered by the Nazi regime, but to remind us to have an accurate understanding of the Holocaust so we can call out the bullshit when we see it.

Here’s what Holocaust distortion looks like, and why you should correct it.

What is Holocaust distortion?

You might be more familiar with the idea of Holocaust denial – the antisemitic conspiracy theory that the Nazi genocide of six million Jewish people did not happen. Deniers believe the Holocaust is a hoax created by Jewish people and allies to gain sympathy and power. This is, of course, objectively false and refuted by mountains of historical evidence.

Holocaust distortion is anything that may “excuse, minimize, or misrepresent” the events and facts of the Holocaust. It is much more common than outright Holocaust denial, and is often less clear-cut – making it potentially more harmful to the Jewish community.

One of the key distinctions between Holocaust denial and distortion is intent. Holocaust denial is an intentional and deliberate attempt to create hatred towards Jewish people and justify Nazism. However, Holocaust distortion is not always intentionally antisemitic – it can also come from being uninformed, and even well-meaning people can find themselves participating in dangerous distortions.

You might have even taken part in Holocaust distortion. It includes things like:

- Making comparison to other atrocities – like the persecution of Uyhgur Muslims in China – which typically misrepresents the details and severity of both

- Using words like Holocaust, Nazi, or Hitler to describe injustices, real or perceived – for example, calling meat-eating an ‘animal Holocaust’, or saying “It’s like Sophie’s Choice” about frivolous decisions

- Celebrating entertainment and media that misrepresents the facts, paints shades of grey over who the victims are, or creates sympathy for the perpetrators. One of the most famous examples of this is The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas.

The way the majority of Australians learn about the Holocaust – at school and from pop culture – contributes to distortion. Dr Rebecca Kummerfeld, Head of Learning at the Sydney Jewish Museum, says these sources often focus on the perspective of the perpetrator which limits our understanding of the history. “You learn about what the Nazis did, you learn about the Nazi law, you learn about the Nazi propaganda, and that’s only one side of the story.”

Dr Breann Fallon, Manager of Student Learning and Research at the Sydney Jewish Museum, adds that education and media typically only exposes us to the most ‘famous’ parts of the Holocaust. “There’s a lot of emphasis on certain countries or certain experiences, and it’s really important to not minimize the Holocaust by only focusing on certain aspects. When I first started at the museum, there was an exhibition about the Holocaust in Greece. And that’s not something that I’d had on my radar.”

“We minimize the Holocaust by only looking at certain countries, we need to broaden our perspective. There is a magnitude to the Holocaust, and let’s be honest, it’s such a big complex history. We’re never gonna understand it all. But to do proper justice to the history we have to look at the expansive geography, multiple victims, multiple perspectives, and make sure that everybody’s voice is heard.”

Whether intentional or not, distortion feeds into the idea that the Holocaust wasn’t as serious. It’s a slippery slope to believing more hurtful and false ideas about Jewish people today.

@stuarth2o The Holocaust, White Privilege And The “But Rule.” #authorsoftiktok #holocaustvictims #annefrank #whiteprivilege #holocaustdistortion ♬ Chopin Nocturne No. 2 Piano Mono – moshimo sound design

What should we do when we see Holocaust distortion or antisemitism online?

That old saying ‘sticks and stones may break my bones but words can never hurt me?’ Yeah, it’s obviously not true. “What we learn from the Holocaust is that genocide starts with words. These ideas were presented by the Nazis, and enough people said nothing, allowing it to grow and emboldened those who felt it was right,” Dr Kummerfeld says.

With digital platforms accelerating the spread of words and ideas so much faster than the 1930s, to combat this happening ever again we can’t just be bystanders – we have to be upstanders.

An upstander is someone who takes action in support of someone being attacked, and against the attacker. That can be as simple as reporting misinformation and antisemitic content, or commenting to correct distortion when you see it.

If you think you’re too small to make a difference, she points to the example of Denmark. They negotiated with Sweden for their Jewish community to travel across the water to hide in the country when the Nazis invaded. People at all levels mobilised to help with the effort, including ambulance drivers, bakers and other workers with vans, and fisherman with boats, and the vast majority of Danish Jews were saved.

The same collective upstander effect works online right now. “It didn’t matter whether people had high status positions in society, but with every individual a movement starts to grow. You’re not one voice against many – you’re actually a community fighting for what’s right and fighting for human rights.”

Of course, to be able to call it out we have to be educated on the facts ourselves. There are lots of initiatives that preserve the first-hand testimony of Holocaust survivors, including the Sydney Jewish Museum interactive ‘Reverberations’ exhibition – which uses AI to have three survivors answer your questions directly.

To take it a step further, Dr Fallon encourages us to be curious and learn about broader Jewish culture too. “The Holocaust is one part of Jewish history – Jewish culture and tradition is so rich and it’s important to learn about that too. That’s a really joyful part of the education! It’s not just about calling it, but also about championing other cultures, whatever culture that may be. It’s also about standing up with positivity to celebrate other people as well.”

Comments are closed.