There is a quietly insidious change happening to the way we talk about ourselves and each other online. You might have noticed it hiding within the seemingly harmless BeReal prank, where you ask someone to take your photo without letting them know the app will simultaneously take their selfie too. When the person unwittingly taking an unflattering snap of themselves is a parent or grandparent, it’s kinda cute. They don’t understand the app, but once let in on the joke they get to laugh along with you and your followers. So silly!

It gets murky when the person asked to take the photo is a stranger (have they consented to you posting their image online, unflattering or not?) A quick search on TikTok shows lots of these videos, some with millions of views, asking random people in the supermarket, on the street, or staff in bars and restaurants to take secret selfies. At one stage, BeReal’s growth strategist David Aliagas was publishing his own series on the app’s official account.

Not all the videos are openly mocking those roped into the prank – hot strangers are, of course, hyped and praised – but many intentionally target people who the anonymous viewer is clearly supposed to snort-laugh at: people who don’t meet societal beauty standards, including (and especially) the elderly. Aliagas’ videos had a noticeable pattern: none of the strangers were white, and they were all working in service jobs at locations where he had more power than them as a customer and tourist.

@johnluther00 NPCReal, “oh sure 🤓” great guy💯 #fyp #SplashSummerVibe #ShowUrGrillSkillz @BeReal. ♬ original sound – Papa John

On its own, the trend is mean-spirited in a juvenile way. But the language used in it hints at a bigger and more worrying shift taking place online: “BeReal with an NPC”. It brands strangers as Non-Playable or Non-Player Characters – a term for characters in video games that the user can interact with in very limited ways, but cannot be played and have no meaningful storyline of their own. They’re simply tools to advance the plot for you, the player. There is nothing wrong with this concept in games, but applying the label to real human beings is gross and dehumanising.

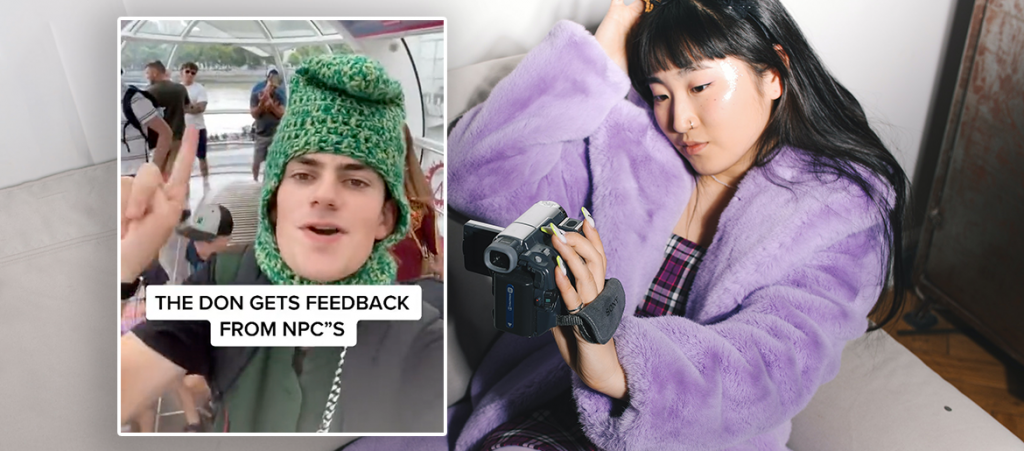

Creator @BigCTheDon, whose real name is Cosmo, is perhaps the most brazen case study of what so-called NPCs are expected to tolerate in real life for the sake of content. He’s kind of like a performance artist whose medium is interrupting people with off-putting, weird and disruptive behaviour; Cosmo’s trademark is making strange noises and loud rants in busy elevators or train carriages. According to him, it’s comedy and an exercise in confidence and unselfconsciousness.

@bigcthedon education is key #fyp #prankingnpcs #npc #foryou #foryoupage #woodnymphs #viralprank #bigcthedon #bigc #npcprank #joker ♬ original sound – Cmeister (Cosmo)

To be clear, I don’t think Cosmo’s on-camera outbursts are dangerous or that people subjected to it would be scared in any meaningful way. He’s a weird guy; you’ll either be entertained, indifferent or irritated. But the language this content is wrapped up in presents the sneaky idea that the public captured in these moments aren’t quite like real people. They are features of the external environment for Cosmo to play with; extras on a set who exist only to react to his wild improv.

NPC is far from the only term we’re using to do this. There are a host of phrases eagerly co-opted from theoretical media analysis that are now completely normal ways for young people to think and talk about their lives.

Do you have Main Character Energy or are you a Side Character? Do you dress for the Male Gaze (a concept specifically created to analyse depictions of women by men in literature and visual arts) or the Female Gaze, despite the fact this term has nothing to do with dressing yourself? Oh, and girls, did your brunch chat, that tense phone call with your mum, or your last performance review pass the Bechdel Test?

The most ridiculous of these misapplied media concepts is asserting whether someone, maybe even yourself, was Written By A Man or Written By A Woman. In literature analysis, it is useful to critically examine differences in the ways characters and stories are written by male compared to female writers. Differences in technique and style influence entire genres, feeding into the social dynamics of the audiences who engage with it.

Like NPC, it’s a term meant for characters, not real people. But young women in particular have taken the concept and run with it, applying it to celebrities and sometimes phases of their own life. The qualities these categories are supposedly standing-in for are clumsy. ‘Written by a man’ seems to loosely cover men with traditionally masculine looks or characteristics (Chris Hemsworth, Joe Rogan), women with obvious sex appeal (Megan Fox), and anyone chasing traditional markers of success (techbros). ‘Written by a woman’ applies to anyone with traditionally feminine looks or characteristics (Emma Watson, Timothee Chalamet), and sensitive, artsy types (Kurt Cobain and, apparently, Harry Styles).

By examining real people, including ourselves, through a lens intended for media analysis, we become two-dimensional. Characters don’t have agency, their actions, interests and beliefs are given to them by whomever created them. Talking about ourselves as if we also have been given a set of characteristics or a plot line to play out, implying that we’ve been authored by someone other than ourselves, is taking part in our own dehumanisation.

Online, if we are just a character then it’s okay to be treated like we are not real. After all, fictional characters in every medium are put through horrible things in the name of entertainment. Does that signal permission for others to do it to us, and make it easier for us to do it to others too?

Social media and showing up online is inherently attention-seeking. It would be all too convenient to wave this away as a symptom of a self-obsessed population, posting on platforms that reward navel-gazing behaviour. The more difficult truth is anything that normalises viewing other people as non-human, even just a little bit, has serious ramifications.

“Why can’t we call y’all females that’s what y’all are” pic.twitter.com/PsPhtF7aiV

— Dreadful Rebel (@Dreadful4Tymes) October 6, 2022

Dehumanisation underscores the most destructive beliefs and ideologies – misogyny, racism, classism, homophobia and transphobia, fatphobia… Believing that marginalised groups are, at best, not deserving of equality and at worst, not worthy of life, is rooted in not seeing them as human. It’s what emboldens perpetrators of discrimination and violence to act they way they do.

Language is a powerful tool for stripping people of their humanity, communicating those beliefs and helping to keep them alive. Overtly destructive speech is usually taken seriously enough to generate outrage and criticism when it enters the mainstream, which is why just one month ago schools were sending parents info packets warning them about Andrew Tate. We try to tackle it, to eliminate it, directly.

Small shifts in language are less attention grabbing, but they so effectively dress up dehumanisation in silly jokes, fun trends and new technology to prime our brains for more hateful or reactionary ideas. Borrowed terms can be twisted into new meanings, repeated over and over until they cause subtle shifts in perception that stick.

We should push back against that. We should refuse digital dialects that tease the idea we are not real people. Being intentional about how we talk about ourselves and others is fundamental to healthy, safe communities. It is that deep.

Comments are closed.