With words like trauma, triggered and phrases like ‘we’re all on the spectrum’ being increasingly used in everyday vocabulary, it’s easy to forget that much of the language we’re using is clinical. What impact is that having on how we view clinical terms – as well as the disorders and symptomatic behaviours they are meant to help diagnose? The rise in therapy-style content on social media platforms – especially TikTok, Instagram, YouTube and Pinterest – can be a double-edged sword. On one hand it helps make the process of diagnosis and support more accessible; on the other, the overuse of clinical terms on social media risks pathologising behavior and turning lived experience into content trends.

Speaking with provisional psychologist Ash King, we look at the significant impact of clinical terms being thrown around on various social media platforms and the rise in ‘insta-therapists’ influence on clinicalised terminology

What are clinical terms?

When we talk about ‘clinical terms’, we’re referring to the specific language used to classify observations of a patient that leads to potential diagnosis, based on those observations and diagnosable symptoms.

When it comes to mental disorders in Australia, GPs can only make a basic assessment – it’s when they refer you to a counsellor, psychologist and psychiatrist that you can ultimately get the assessments needed to help create the language that describes your situation.

So while many people do suffer the symptoms of mental health disorders and may very well experience anxiety or feel out of place in social situations, this does not necessarily automatically equate to an anxiety disorder or autism spectrum disorder.

When talking about the slow takeover of clinicalised terminology in our everyday Ash explains, “we’re getting to a point where the term ‘trauma’ is now being applied to any unpleasant experience, or the use of the word ‘triggering’ when referring to the dude sitting behind you on the bus who’s chewing his gum loudly.”

This impact those with serious chronic conditions, by diluting how these terms are understood. “It dispossesses people living with the chronic and debilitating reality of such conditions, removing the necessary language through which to make sense of their own, often difficult and isolating, experiences,” Ash says.

@latearareads FYI this is a joke (also not accurate) 😂 based off of a conversation I had with a friend of mine 🥰 #booktok #reading #booktropes #foryou ♬ everyone using this sound – zup

Self Diagnosis vs Clinical Diagnosis

Getting a formal diagnosis often comes with privilege; in Australia the cost of the process to even see a psychologist or psychiatrist is prohibitive. And, with long waitlists before you can access help through the public or private systems, it’s no surprise that many are leaning into social media content and self-diagnosis.

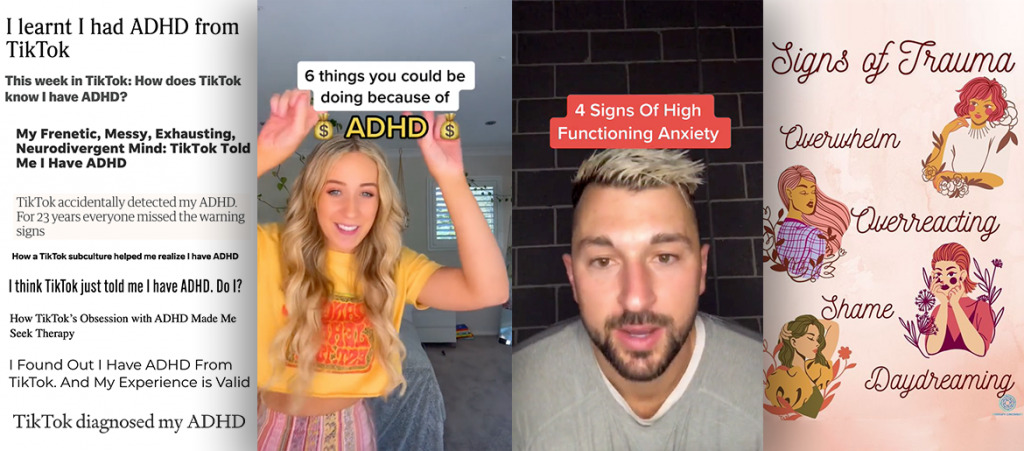

Enter: insta-therapists and mental health TikTokers with massive followings.

Social media provides a free and accessible way for those searching for answers’ to access what appears to be quick and easy therapies, giving new and relatable vocabulary to a large audience. But TikTok in particular has seemingly become the wild west of medical professionals and therapists. On social media anybody can claim to be a doctor or a therapist with very little evidence, and present information to their audience by using clinical terms and sentences that feel correct. That’s why Micheline Maalouf, a TikTok therapist with a huge following, is campaigning to have verification badges for qualified mental health practitioners.

When clinical or therapised language becomes very mainstream, it starts to crop up in topic areas seemingly unrelated to mental health – further diluting its intended meaning and use.

Ash and I both agreed that this created a great way for people to normalise discussions on mental health and therapy, and a new opportunity to share lived experience. However, there are a few things to be considered. “Do social media platforms, with their associated limitations – such as one minute time cap on Tik Tok, or caption-character limits on Twitter – offer an adequate forum to share and discuss the nuance and complexity that is inherent to mental health and well-being?”

Social media can be tricky, allowing for claims being made as “fact” without verifying its legitimacy. Ash explains the risk this presents is when we start to self diagnose without the intricacies that a diagnosis requires.

“You could diagnose yourself with a mental health condition and neglect exploring potential physiological components that are relevant. Like diagnosing yourself with ‘panic disorder’ and missing a relevant diagnosis of hyperthyroidism or irregular heartbeat. Or you could over-diagnose yourself with a disorder, believing that feeling stressed about upcoming exams means you have an anxiety disorder, or fidgeting and struggling to focus on work constitutes a diagnosis of ADHD.”

So, are we overusing clinical terms on social media or not?

Well, yes and no. Expanding our terminologies and educating people about mental health and disability issues is important. It’s validating, supportive and empowering.

It’s especially important for women, non-binary and transgender people as the medical field and its diagnosis framework for mental health and neurodiversity has long focused on men and boys. For example, historically girls were only classified as neurodiverse if they exhibited extreme presentation, and diagnosis for adult women was (and still is) rare. Only in the past 10 years have we’ve started slowly starting to see gender equality in the diagnosis process.

But watching a clip on TikTok or a 30-minute YouTube video that is relatable shouldn’t be justification to start acting and speaking as if we are diagnosed. “The truth is diagnosing and working with mental illness requires a detailed understanding of behaviour, context, impact, history, substance-use and many other internal and external factors,” Ash explains.

Having more open discussions around therapy and deconstructing the stigma around clinical terms is a positive step. But we need to be more considered about how and when we use terms like anxiety, trauma, neurodiversity or major depressive disorders. Is hearing a co-worker loudly chew their lunch “literally traumatising”, or do you simply not like it? Will it affect your ability for function in the longterm, or will you have forgotten about it by dinner?

Loosely throwing around these words can hijack the necessary language needed for those with chronic conditions, and de-legitimise their ability to express a sense of self in an already isolating and difficult experience.