Universal Music Group (UMG) has removed its entire catalog of music from TikTok, after the two companies failed to agree on new contractual terms – you already know this. But it’s been fascinating to both sides attempt to justify their stance. One one side, tech giant TikTok insists that the exposure it offers to artists is more important than fair compensation for art (a stance that users are, surprisingly, endorsing). On the other side, UMG is positioning itself as a champion of artists rights and revenues by rejecting a bad deal. The reality is… there are no good guys in this fight. Both corporations are fighting for a bigger piece of pie, and they’re really only taking from the artists.

The allure of exposure

In an open letter to artists and songwriters, UMG stated that their motivation behind pulling their music, was due to three main concerns: compensation; AI protection and regulation; online safety and harassment. UMG says “TikTok proposed paying our artists and songwriters at a rate that is a fraction that similarly situated major social platforms pay.” The most important aspect of this entire debacle is paying and protecting the work of artists – this should be the number one priority. From that perspective, UMG’s stance seems principled.

But a lot of artists have spoken up against UMG advocating for their interests, because they now rely on TikTok so heavily for exposure. Even though TikTok only makes up 1% of UMG’s revenue, artists say this aggressive stance is preventing them from promoting themselves on what is now a significant cultural meeting place, diminishing their marketing influence and potentially their financial future. Noah Kahan, who went viral on TikTok for his song Stick Season and was subsequently nominated for Best New Artist at this year’s Grammy Awards, expressed his concerns in a TikTok: “I won’t be able to promote my music on TikTok any more … I’ll probably be OK, right? I’ll probably land on my feet, right? Right?”

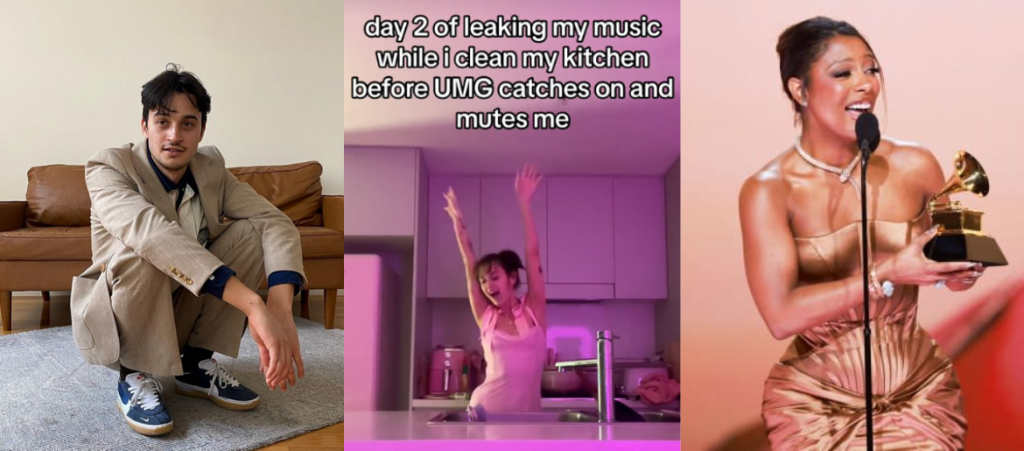

For undiscovered and smaller artists, it’s more complicated. Swaine Delgado is a Melbourne-based artist and producer, who was formally signed onto a label under UMG. Like many others, he woke up on the day to find his whole catalog and “his most successful EP” had been muted on TikTok. Despite this, Delgado has some optimism about the decision. “[Smaller artists] actually have more chance of your song getting picked up, rather than just another billion plays for another huge artist,” he says.

The app’s algorithm-based approach to content discovery has revolutionized music promotion, creating a new avenue for artists to achieve viral success and reach new audiences. Victoria Monet won the Grammy for Best New Artist this year, and like Kahan it came after she was propelled to wider fame on TikTok. For artists outside the mainstream pop and rock genres, the app can be a rocket to stardom, offering visibility and opportunities that traditional channels often overlook.

UMG and its labels know this. Swaine said his old label “would write up programs to do two TikToks a day. Once a month, they’d send us what the trending sounds are on TikTok. The whole thing was that you must be using TikTok if you are an artist.”

@swainedelgado Thanks for the template @The Beaches, literally in the same position. Support your independent! #universalmusic #independentartist #fypシ ♬ Ben 10 Trap Remix by Modagoatt – Mo🐐

What’s music worth?

That’s not to say we should all be on TikTok’s side of this beef. UMG’s claims that TikTok is vastly underpaying for use of music is true: TikTok pays artists 3 cents (US) for each new video that uses your song – not per view, which would be an equivalent to Spotify or Apple Music paying per stream. If 1,000 videos use your song, you will earn $30. The royalties goes through the distributor to the artist, and TikTok has individual agreements with labels specifying how much revenue goes to the artist (UMG has not reported what their labels’ splits are). If music is adding value this tech platform where advertising is sold to make TikTok money, don’t the people providing that music deserve to be fairly paid for it? If a large creator lip syncs to a song, and that video is seen by millions of people, doesn’t the artist deserve to be paid more than 3c?

Then there are the AI concerns, which are as dystopian as those being discussed in the almost 150-day Hollywood strike. AI-generated ‘renditions’ of an artists work – like this rip-off of Drake and The Weeknd that was technically eligible for the Grammys – abuses their intellectual property, reduces their creative autonomy, devalues their work, takes revenue away from them and can potentially harm their reputation. While TikTok has introduced new labelling requirements for content that includes any traces of AI, the amount of Glee renditions of new songs that appear on my FYP tells me this isn’t being enforced or taken seriously.

Even on the topic of discoverability, TikTok is not afraid to sacrifice the artists it claims to ‘help’ in the pursuit of saving some cash. UMG says TikTok has removed the music of some of UMGs smaller artists audios from the platform as part of an intimidation strategy, to “bully us into accepting a deal worth less than the previous deal, far less than fair market value and not reflective of their exponential growth.”

If TikTok’s arguments – about being committed to discovery, celebrating artists and helping fans connect with music they love – sound familiar, it’s because they’re used by another exploitative tech giant: Spotify. The maths works out to about 0.03c to 0.05c per stream to music distributors (who take their cut before paying royalties to artists). Swaine says that accessing music for free through different streaming services helps maintain “connection to fans and longevity as an artist,” but the compensation is so low that it’s impossible to survive unless you’re getting huge streaming numbers.

It’s why Taylor Swift, the queen of arguing the commercial value of her art, famously pulled her own music from the platform in 2014. At the time, she wrote in the Wall Street Journal: “Music is art, and art is important and rare. Important, rare things are valuable. Valuable things should be paid for. It’s my opinion that music should not be free, and my prediction is that individual artists and their labels will someday decide what an album’s price point is.”

Of course, there are only of handful of artists who are in Swift’s powerful negotiation position. The rest (even very famous ones) are being forced by giant corporations on all sides to choose between exposure and fair compensation.

As fans and consumers of music, we’re involved in this struggle too. While many TikTok users are making (mostly lighthearted) videos about how annoying it is not no longer have good music to use for fan edits, makeup transitions or day in my life vlogs, very few of these mention the predicament of the artists. Should we have access an artist’s work for free? If we expect Spotify, TikTok and corporate industry giants like UMG to genuinely prioritise artists, why are we not doing the same?

Is there any hope for artists?

At the core of this conflict is greed. The two major players have a foundational clash of interests: UMG wants to maximise revenue by increasing its control of how music is used; TikTok wants to maximise revenue by paying as little as possible for the music that contributes to user engagement and retention. As consumers we have financial skin in the game too, although it’s secondary and not motivated by greed. We understandably want to pay as little as possible to enjoy the music we love – living is expensive! But our desire to keep costs down has contributed to the industry’s undervaluing of music artists.

The big corporations involved can afford to go back and forth on artists’ livelihoods but the artists themselves cannot.

Before the streaming era, the only way to legally access music was to buy a CD or pay to download songs on iTunes – a more direct way financially support our favourite artists. While we have little influence in the TikTok vs UMG battle, we can return to these ‘old school’ habits to support our faves through this rough time, especially those who are independent and just starting out in the industry. Delgado says the best ways to support indie artists is to “find a way to buy their music, like on Bandcamp” and buy merch because the money typically goes straight to the artist.

The future of music distribution hinges on crucial discussions surrounding fair compensation, protecting artist rights, and redefining the role of record labels in shaping these negotiations. Whether or not it came from pure intentions (it definitely did not), UMG’s decision to withdraw from TikTok should spark a long-overdue revamp of how this all works. Maybe a future music ecosystem where artists, songwriters, composers are able financially supported to make great art will trace its history back to this very moment? Here’s hoping.

Smart people read more:

The TikTok-UMG Power Struggle: What is Music Without the Short-Form Video Platform? – Centennial World

Universal Music’s Fight With TikTok Is Screwing Indie Artists – Vulture

The Latest Victim of Everything-Is-Content? Festivals and Live Music

Comments are closed.