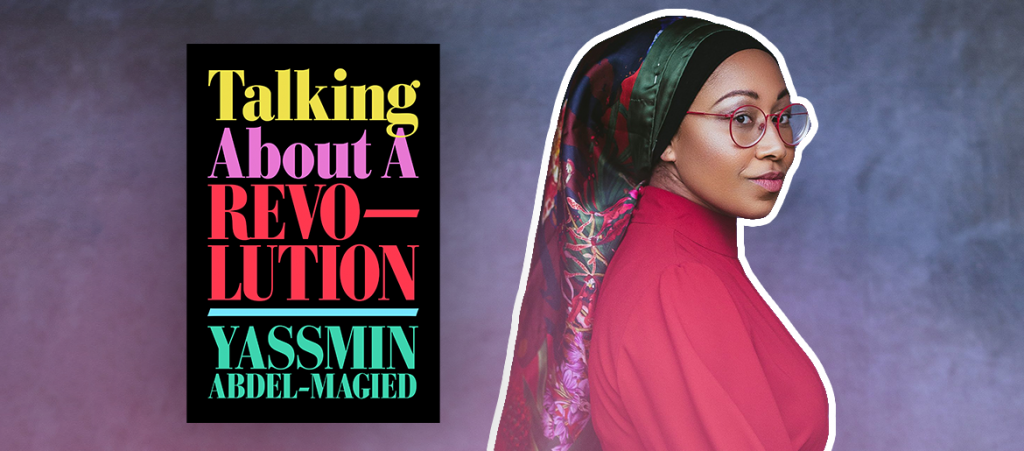

Yassmin Abdel-Magied has lived out many storylines just three decades: migrating from Sudan to Australia with her family as a baby; working on oil rigs as a young woman; becoming a public figure, then a ‘villain’; and now working as a writer in Paris and London. Any one of these seasons of life could be a movie or a book on its own, but that’s not her style. Abdel-Magied’s work has always focussed on creating a “fairer , safer and more just world”, and that’s exactly what underpins her new book, Talking About a Revolution.

This collection of essays – some old, some brand new – will change the way you think about the world, and how we can change it for the better. It’s about growth, identity, language and progress. If you’re feeling deflated or despairing about the state of *all of it*, Talking About a Revolution is a shot of energy. A shake up.

We spoke to Abdel-Magied about personal growth, political change, and how to stay optimistic through it all.

Who most needs to read Talking About a Revolution?

Young people who really care about the world and are looking to deepen their understanding of it in a way that helps them move through it. And who are interested in social change, resistance and, you know, revolution for lack of a better word.

I remember when I was in my teens and early twenties, I was constantly kind of trying to find ways to think about what was going on in the world around me and a lot of the people that I read were from the civil rights movement or from earlier movements. We are going through our own version of that in the 21st Century. So I guess it’s a book for people who want to be part of that and be guided through that thinking.

Some of the essays in the book were written almost 10 years ago. What was it like to revisit those now?

I think it’s a nice thing to be able to see how much I’ve grown. And it’s important for people to see because it shows that one’s approach and thinking and politics can change so much over time. I wanted to chart people through the evolution of my own politics… Like, I didn’t pop out of the womb a fully formed political being! It took a long time for me to learn all sorts of lessons.

That 22-year-old version of me was a lot more optimistic and wide eyed and bushy tailed. There was also a lot of stuff where I realized looking back that I really did understand the world differently, and I wouldn’t agree with that position anymore.

The book is split into two sections: changing our internal ‘self’, and change in the external world. The idea is that you need both for revolution to succeed… Do you think people achieve the right balance of internal work vs external work?

I think the challenge is that we are quite often focusing on what we can control most easily. Focusing on the individual “work” is certainly part of the puzzle, but it’s a bit of a red herring in the sense that social transformation cannot happen without structural and systemic and material change, right? Like you can do all the therapy in the world, but if people literally can’t afford to eat that that’s not really a solution.

We live in a world that operates on these neoliberal approaches – the idea that you’re a piece of capital or an asset to be optimized. As somebody who grew up doing very sort of unsexy, grassroots community work, I think part of the reason that it’s easier to focus on the individual internal stuff is because you can then tell a story about it. Whereas the grassroots collective, capacity building and organizing can be very time consuming. There’s only so many TikTok or Instagram posts you can make about your six hour community meeting in town hall every week!

That’s what I mean when I say it isn’t set up for the way that we are incentivized, the way that we’re rewarded – it’s not for collective work. We’re rewarded for showing what we as an individual are doing. If we can shift our perspectives a little bit, that can hopefully help.

There is an element of hope and optimism that comes through the collection, which was kind of surprising. How do you keep that belief and not get sucked into the despair?

To be honest, I swing wildly between being a hopeful, optimistic to a real dark cynic. But I probably wouldn’t do what I do if I didn’t think a better version of the world was possible.

So I almost take an engineer’s approach to that. I’m like, all right, what do we have to do? It’s not about being optimistic or pessimistic. It’s about assessing the situation, finding out what the challenges and obstacles and systemic roots are. And then thinking about how we go about doing it differently. Obviously there’s a really emotional aspect, but also there’s a part of me that is able to step slightly back and assess it as if it’s an engineering problem. That gives me some relief, the process of thinking about things as systems.

How does Australia look to you, now, from a distance?

It’s tricky. Before the election, Australia had really damaged its international reputation. When it comes to asylum seekers, climate change, the media landscape, the obsession Australia has with borders… A lot of that stuff hasn’t actually made sense to people overseas. Especially in the US, UK, and France where I was last year, people see Australia in a similar bucket to them, and they’re like “This is weird behaviour. What’s going on down there?”

With this election… The jury’s out, I think the jury’s really out. It’ll be really interesting to see how the next few years pan out for Australia. I think people are right to have some sort of hope and optimism or be proud of the fact that they have been able to depose Scott Morrison’s government. But the work has just begun.

What’s really interesting is seeing the city that I grew up in, Brisbane going green. It does make me think, okay, maybe there are some sort of more fundamental shifts here that we’re gonna see pan out over the next few years. And what will that mean for the country? You know, it’s all up for grabs.

What do you hope people will do with the ideas after they’ve read the book?

Part of why I wanted to call it Talking About a Revolution is because I think that I really want people to have conversations that move forward in some way. Quite often we have these really circular conversations about similar topics that don’t really make us think more deeply about anything.

So I want people to share it with others and talk about the ideas. Really think about “What do I actually believe in? What is it that I actually stand for?” For me, I know that I care about justice and it’s informed by my faith, by Black feminist politics, philosophies around abolition and so on. I know that, but it’s taken me a long time to actually know what my values are and therefore, what kind of world I wanna build.

That’s what I want people to do – talk about revolution, dig into it, to figure out what they actually believe, so that when we go out and fight, we’re all on the same page.

Yassmin’s Favourite New Essays in Talking About a Revolution

‘To All the Cars I’ve Loved Before’: “This is about my long love of petrol cars and the heartbreak of coming to accept that the era of the petrol car is over. So this was like a eulogy to the petrol car, almost like a love letter in a sense. It’s quite emotional in lots of different ways and different to how I’ve written things before.”

‘Whose Borders Are They?’: “This was probably one of the more difficult ones – this, and ‘Islam and Social Justice’ were the most difficult ones for me to intellectually wrangle. I talk about the idea of un-belonging, and challenging the idea of borders and the nation state. There’s some really original stuff in there that I’m proud of introducing to that discourse.”

‘Words Mean Things’: “It’s just a really fun read! It’s a bit cheeky. You know, you get some philosophy, you get some like Yassmin history… That’s why I wanted to start with it, ‘cause it’s a nice insight into what you’re gonna get in the collection, but also a little bit into who I am.”

Talking About a Revolution is available now.

Comments are closed.